The broad context

A dredge is a tool. For hundreds of years this tool has been used to shape and manipulate the interface between land and water in order to support a variety of human activities, including navigation, coastal protection, flood risk management, as well as residential, commercial, agricultural and hydro-power development. The use of dredging to achieve these purposes has always been guided by an understanding of the costs and benefits of applying the tool. However, in the last few decades the understanding of what constitutes costs and benefits has evolved substantially beyond the direct monetary costs of using the tool and the direct monetary benefits of what the tool was used to create.

This evolution was aided by the environmental movement over the past five decades, where the costs (in a broad sense) of applying the tool was expanded to include the negative environmental impacts that can be associated with dredging. Environmental regulations were put in place in an effort to minimise negative impacts on ecosystems caused by dredging activities, and for the last few decades dredging has been at the centre of a conflict, where the water meets the land, between groups supporting development and the environment. However, attitudes and approaches are changing.

The environmental regulations that have been put into place over the last 50 years to eliminate, reduce, or control the impacts of dredging on the environment, have produced a range of outcomes, both positive and negative. It is undoubtedly true that such regulations have helped to reduce negative impacts on the environment, in general. However, it is also true that the amount of environmental benefit produced by these regulations has not been systematically quantified, nor have the environmental, social and economic costs of such regulation been fully assessed (e.g. related to trade-offs and transferring impacts within the system). Today, a paradigm shift is being embraced – a move toward a holistic approach for integrating values for people, planet and profit.

The growing focus on sustainability

The international focus

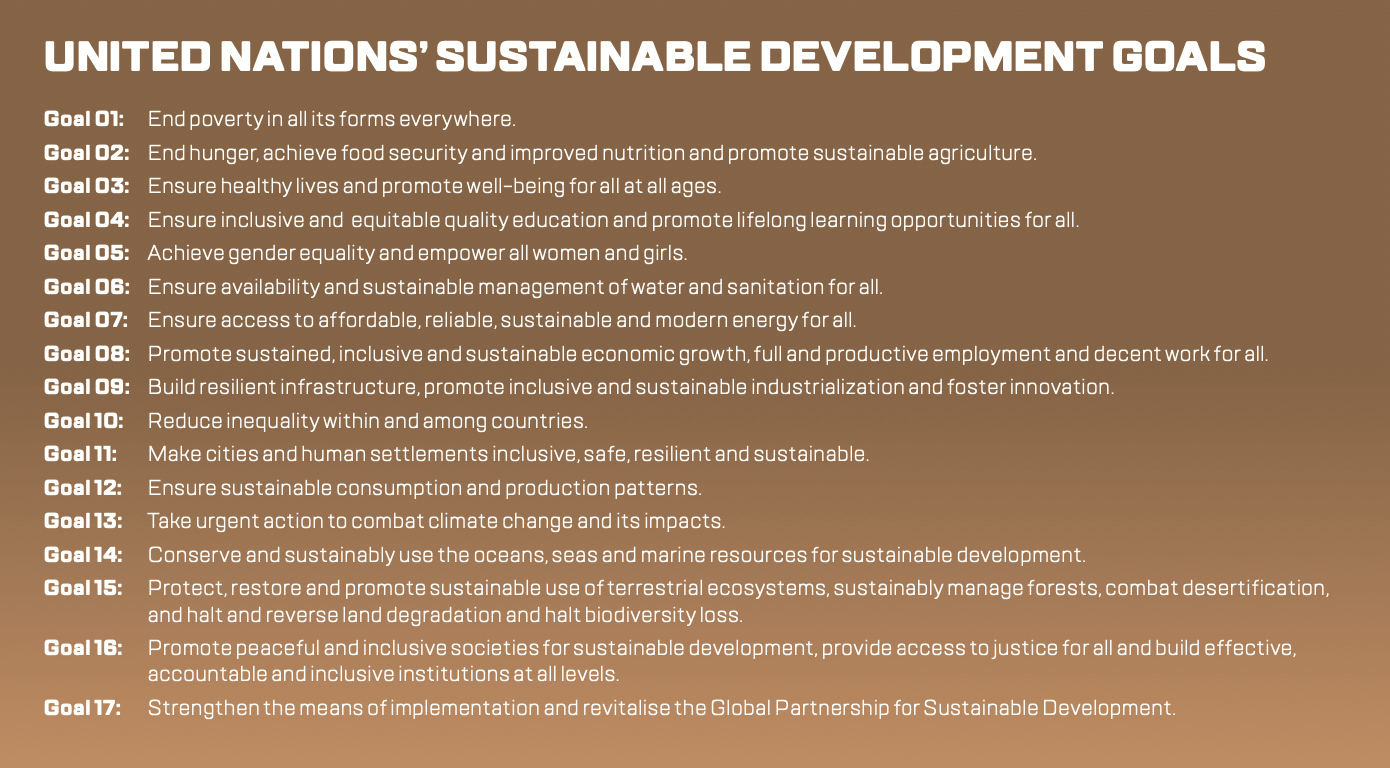

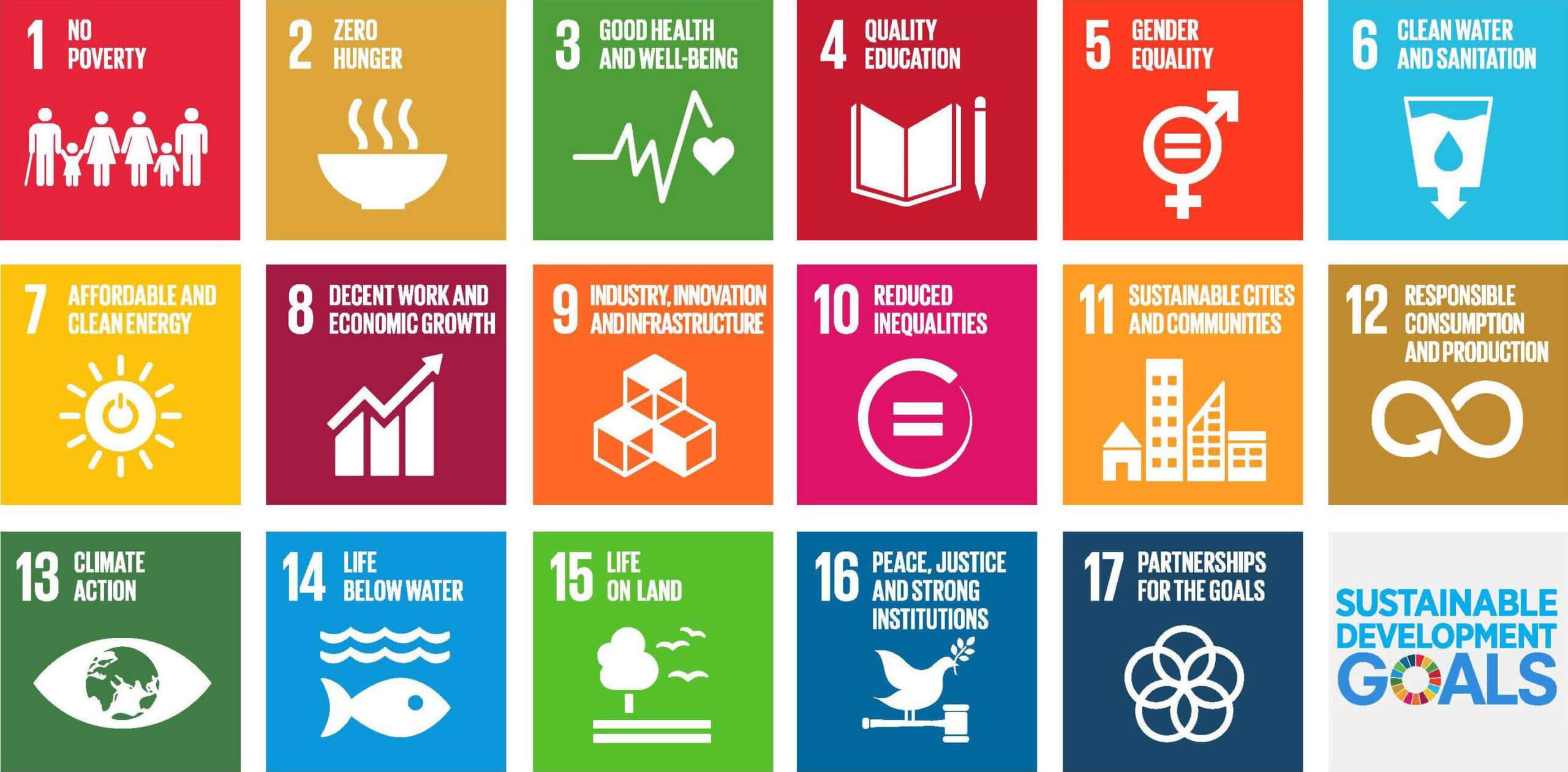

An increasing amount of attention is being given to the concept of sustainability as an approach to informing social, environmental and economic development. In 2015, the United Nations (2015) published its SDGs, as a part of “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (see Figures 1 and 3). These 17 SDGs encompass a very broad range of interests, values, and objectives.

As a means for developing water resources infrastructure, the relationship of dredging to each of the 17 SDGs varies. For example, the use of dredging to construct efficient and productive navigation infrastructure is directly connected to SDGs 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, and 15. As a tool used to provide coastal protection and infrastructure supporting flood risk management, dredging clearly supports SDGs 1, 3, 6, 9, 11, and 13, among others. In the future, one of the opportunities that should be addressed by the dredging and water infrastructure community is to incorporate these goals into the infrastructure development process, while effectively communicating how such projects support the SDGs.

The organisational focus

An example of organisational focus and application of sustainability in relation to dredging and infrastructure can be seen in the Environmental Operating Principles (EOP) of the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The USACE dredges approximately 250 million m3 of sediment annually (including permits for dredging issued through its regulatory programme). This level of dredging supports a network of nearly 40,000 km of navigation channel and the associated ports, in addition to flood risk management and ecosystem restoration projects. In 2002, the USACE developed and published its EOP, which were subsequently updated in 2012.

These principles were developed and disseminated by USACE as a means of advancing its stewardship of air, water and land resources while protecting and improving the environment. These principles have been communicated within USACE and codified as a part of an agency regulation so that each of the more than 30,000 employees of the agency “understand his or her responsibility to proactively implement the EOP as a key to the Corps mission.” (Bostick, 2012). The USACE EOP recognise the relationship of infrastructure development to the three pillars of sustainability, the importance of considering the long-term, life-cycle implications of agency actions, and the essential need to openly engage the stakeholders and interests affected by its projects and programmes.

The sector-specific focus

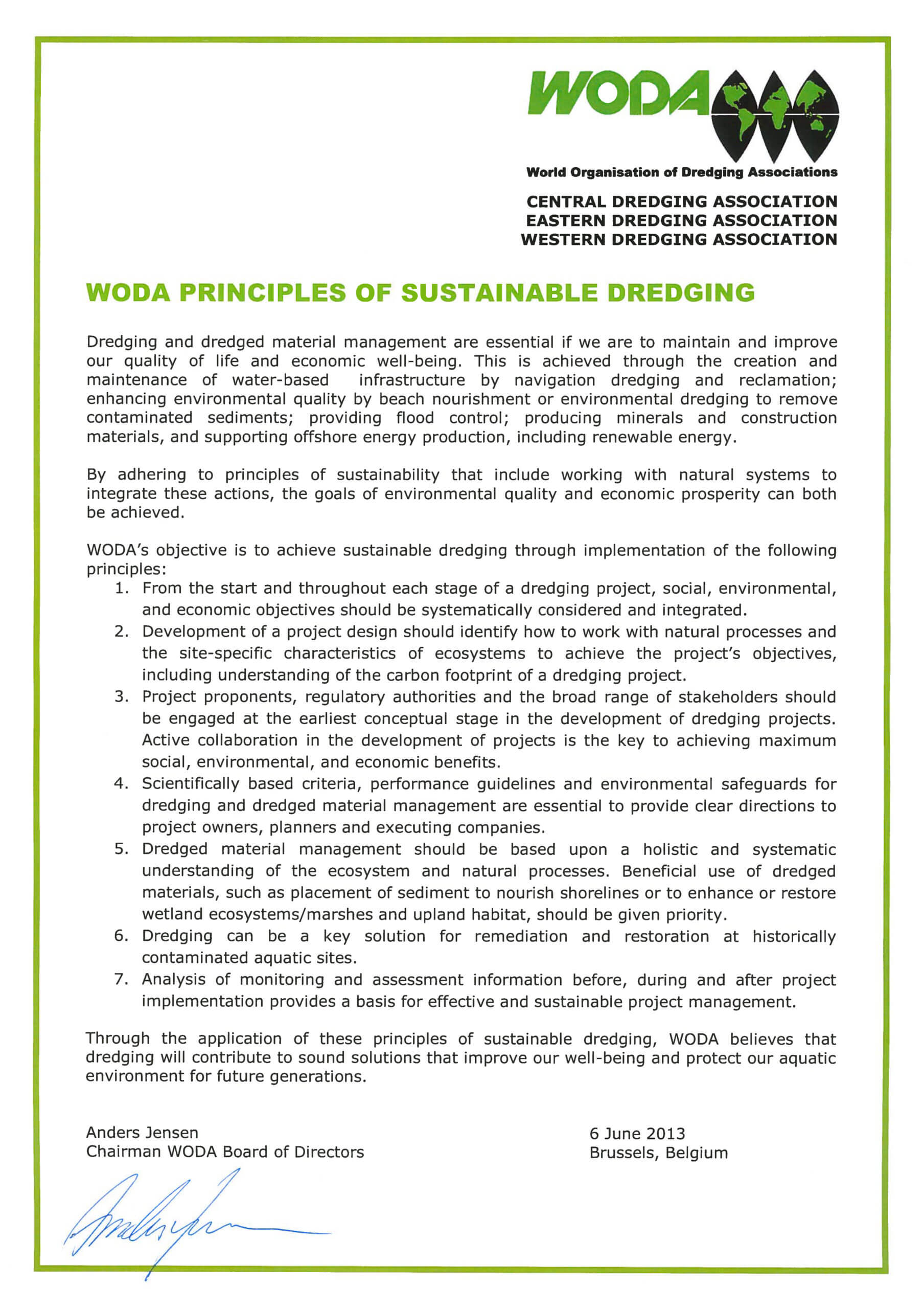

In 2013, the dredging sector itself, through the actions of the World Organization of Dredging Associations (WODA) (which includes the CEDA, the Eastern Dredging Association (EADA), and the Western Dredging Association (WEDA), published its principles of sustainable dredging (see Figure 4).

The WODA principles reflect the importance of using dredging to create value across the three pillars of sustainability, considering the system-view of projects, including the ecosystem and natural processes operating within the system, and the role of engaging stakeholders (including project proponents, regulators, and the broader array of interests relevant to a project). Publication of the WODA principles has sparked a range of discussions and actions within the dredging sector in efforts to seek a balance between the economic development that is supported through dredging and environmental considerations and regulation.

Also, the recently published technical report “Sustainable ports: A guide for port authorities” (PIANC, 2014), from the port sector illustrates this shift towards an integrated and sustainable approach. This guide is a joint report of The World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure (PIANC) and International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH). It defines a sustainable port as “... one in which the port authority together with port users, proactively and responsibly develops and operates, based on an economic green growth strategy, on the Working with Nature (WwN) philosophy and on stakeholder participation, starting from a long-term vision on the area in which it is located and from its privileged position within the logistic chain, thus assuring development that anticipates the needs of future generations, for their own benefit and the prosperity of the region that it serves.”

With regards to sustainable dredging it states the following aims: The Green Port goals related to sustainable dredging are primarily to keep the port’s nautical access open, clean and safe. At the same time, the goals aim to:

- manage integrated dredging activities to create opportunities for improving environmental quality and at the same time creating or enhancing ecosystems;

- manage dredged material according to the philosophy of minimising quantity, enhance quality, reuse with or without pre-treatment and long-term beneficial placement; and

- understand the local (and surrounding) environment and search for opportunities to use the natural processes including hydraulics, hydrology, geophysical, vegetation, benthos, etc., to maximise the efficiency of the dredging in both the short and long term.

Applying the concept of sustainability to water infrastructure development

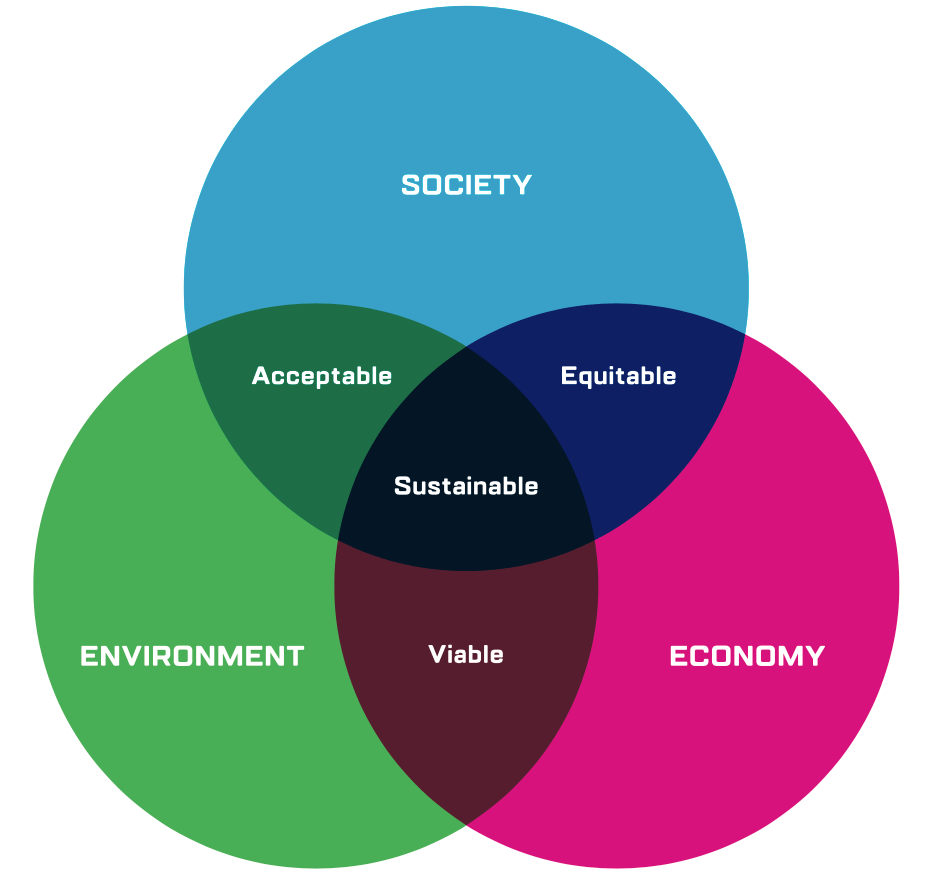

The concept of sustainable development is based on the premise that the design for an action (in this case a development project that involves the use of dredging) will be informed by a full consideration of the values and costs of the proposed action across the three pillars of sustainability: society, environment and economy (see Figure 5).

The concept of sustainable development recognises the need to consider the full range of benefits and impacts related to human actions and the distribution of these benefits and costs across the social, environmental and economic domains. The relationships among these value domains are reflected by the goal to take actions (e.g. develop projects) that will balance the distribution of benefits and costs so as to produce socially equitable, environmentally acceptable, and economically viable outcomes. This balance is achieved through active and consistent engagement with the stakeholders who will be affected by the proposed project, including government authorities, private sector interests, local / regional / national members of the public, and the special interest groups and perspectives that are relevant to the project.

In order to aid our discussion of sustainability in the context of infrastructure development and dredging we propose the following operational definition (in line with the definition proposed by Brundtland et al., 1987): “Sustainability is achieved in the development of infrastructure by efficiently investing the resources needed to support the desired social, environmental, and economic services generated by infrastructure for the benefit of current and future generations.”

Here, we use the word infrastructure to refer to the diverse range of structures, features, and capabilities that are developed through the use of dredging (e.g. navigation channels and waterways, ports and harbours, levees and dykes), and nature-based infrastructure, such as islands, beaches and dunes, wetlands, reefs and many other forms of habitat. In practical terms, the sustainability of an infrastructure project is increased by:

- increasing the overall value of the project through the range of services it provides;

- reducing costs associated with the project, where the word costs is being used in the broadest sense to include all of the monetary and non-monetary (e.g. environmental impacts) costs and resources consumed by the activity; and

- balancing the distribution of the value and costs among the social, environmental and economic domains over time.

Some practical implications for dredging

The importance of vision and value creation

For the vast majority of the history of dredging, the nearly exclusive focus of the activity was to generate the economic benefits produced by infrastructure. The incorporation of environmental and social factors (the other two pillars of sustainability) into the decision- making and governance process is a relatively recent development, mostly concentrated within the last 50 years. During the last few decades, significant technological and operational advancements have been made that have improved the dredging process in relation to the environment. That said, one of the biggest opportunities for increasing the overall sustainability of the water infrastructure sector is for project proponents, dredging contractors, and other stakeholders to invest more time and energy in up-front visioning to identify ways of creating more project value across all three of the pillars of sustainability. Such visioning will not diminish the importance of generating economic benefits from infrastructure, rather, it is more likely to reveal opportunities for creating additional economic value. By devoting more effort to identifying and developing positive social (e.g. recreational, educational, community resilience) and environmental (e.g. ecosystem services, habitat, natural resources) values, dredging and infrastructure projects will be able to avoid unnecessary conflicts with stakeholders while simultaneously developing a larger number of project proponents, advocates and partners.

Adapting projects to nature, rather than the reverse

Dredging is used to change or manipulate the physical structure of the environment to produce a feature or a function that nature did not and would not create on its own. For centuries, ports and waterway networks have been produced by creating a design for these systems and then imposing that design on the natural environment, with mixed results. Traditionally, designs were evaluated for their engineering performance and impacts on nature. Uncertainties related to performance and impacts were acknowledged to varying degrees. In the past, engineering was focused more on hydrology than ecology. In this historical approach, the engineering design and economic costs were dominant factors and effects on nature were secondary considerations. However, important lessons have been learned. Effects on nature and impacts in the coastal zone and rivers were underestimated or partly ignored in many cases. Lack of knowledge regarding sediment processes and the relation of these processes to local and regional geomorphology resulted in negative effects on engineering performance (e.g. higher than expected sedimentation in channels and reservoirs, erosion and scour around structures) and ecosystems (e.g. loss of habitat).

The ability to project long-term performance and effects was complicated by uncertainties. Hard structures, separating fresh and salt water and wet and dry areas (e.g. revetments, breakwaters, dams, walls, dikes etc.), were common engineering solutions, in order to manage the hydraulics. Rivers were trained and dams were built to facilitate navigation, manage high water and flooding, and generate energy. In many cases these solutions have disrupted sediment processes, which have given rise to long-term effects and current, ongoing engineering and ecological challenges (e.g. shrinking reservoir capacity due to sedimentation, shoreline erosion, loss of coastal landscapes and habitats, etc.).

Past engineering projects have certainly delivered major economic, safety and human welfare benefits. As time has passed and the infrastructure projects have “begun to show their age”, the adverse effects associated with these projects have become more and more visible, casting at least a partial shadow over the realised benefits produced by their construction. In view of the processes, variability and extremes associated with climate change, there is renewed motivation to consider the long-term sustainability of water infrastructure.

Nature can be a stubborn and uncooperative collaborator when she is not adequately considered and consulted during the process of design. Winds, waves, and tides deliver force, water, and sediment against the products of our design with endless energy, which prompts us to spend our effort, time, and money reacting to nature’s onslaught. We have learned the lesson countless times that taming nature can be an expensive proposition. Integrating the concept of sustainability into our infrastructure projects will help us identify opportunities to cooperate and collaborate with natural processes, rather than seek to control and counter them. Working in this way we will adapt the port to the coastal ecosystem, the ship to the river, the local community to cycles of low and high water.

PIANC’s WwN philosophy incorporates this approach to navigation infrastructure development and the Building with Nature (BwN) programme in the Netherlands (De Vriend and Van Koningsveld, 2012, www.ecoshape.org) and the Engineering with Nature (EwN)® initiative in the United States (Bridges et al., 2014. www.engineeringwithnature.org) are implementing these practices across a wide range of water infrastructure projects. The opportunity and need to more directly incorporate nature into our infrastructure development process can be viewed at two different levels: the scale of the system the project is part of and the means of constructing and operating the project. Our infrastructure projects are part of a system (e.g. an ecosystem), and the projects will both affect and be affected by the processes operating within that system. The more we are able to take these processes into account over the full life-cycle of the project, the more sustainable the project can be. The more we use construction and operational methods, including dredging, that intentionally incorporate natural processes and materials, the more sustainable the project can be.

The new nature-based design philosophies draw attention to the opportunity and need to enhance natural capital, over the short and long term. As the concepts, techniques and tools supporting ecosystem services are implemented as a part of infrastructure practice, we will be able to communicate about sustainability more effectively within our project teams and with the broader community of stakeholders interested in our projects.

Taking the long view

Water infrastructure projects, due to the amount of investment they require, are long-term propositions. While the state of scientific and engineering practice continues to advance, there will continue to be uncertainties regarding the behaviour of natural and engineered systems over the long-term. Nevertheless, pursuit of sustainable infrastructure requires taking a broad and long-term view of a project’s life cycle. Taking this broad, system view is necessary in order to determine whether the project can be expected to be sustainable over the long term, i.e. that the total value of the project over the three pillars of sustainability is judged to be sufficient in relation to the investment required to create that value. Performing such sustainability analyses could mean that some proposed projects will not be built, or that existing projects will be decommissioned and abandoned in favour of more sustainable projects. Some ports or waterways, for example, which cannot be efficiently sustained over time due to the effects of physical processes, coastal conditions, sedimentation, environmental impacts, etc., would receive reduced levels of investment in favour of ports and waterways situated in a more sustainable condition. When investment decisions are being made on the basis of the overall sustainability of the project, then we will know that the concept of sustainability has been successfully incorporated into the governance of infrastructure systems.

Three guiding principles of dredging for sustainability

Principle 1

Comprehensive consideration and analysis of the social, environmental and economic costs and benefits of a project is used to guide the development of sustainable infrastructure – Dredging is but one component of an infrastructure project, and any one piece of infrastructure functions as a part of a larger network of infrastructure as well as the surrounding ecosystem. Therefore, understanding the full set of costs and benefits of a project requires taking a system-scale view of infrastructure and the functions and services that infrastructure provides.

The costs (in the broad sense) of a project include all the resources, material, and negative impacts associated with executing the project and/or producing and operating the system over time. Likewise, the benefits generated would include all the values, services, and positive outputs generated by the project and/or system over time. Defined in this way, costs and benefits will include both monetisable and non-monetisable quantities.

While traditional economic analysis can be used to develop an understanding of the more readily monetised costs and benefits, for other values within the social or environmental domains different methods should be used to develop credible evidence about costs and benefits. Finally, one of the key opportunities for increasing the overall sustainability of water infrastructure is to seek opportunities to increase the total value of projects by identifying and developing benefits across all three of the pillars of sustainability.

Principle 2

Commitments to process improvement and innovation are used to conserve resources, maximise efficiency, increase productivity, and extend the useful lifespan of assets and infrastructure – Innovations in technology, engineering, and operational practice provide opportunities to reduce fuel and energy requirements related to dredging and the operation of infrastructure. These same innovations can provide the means to reduce emissions (including greenhouse gases and other constituents) and conserve water and other resources.

By reducing the consumptive use of resources associated with dredging and infrastructure the sustainability of projects is enhanced. In addition, using better technologies or improvements in operational practice in order to extend the useful lifespan and functional performance of an asset (e.g. a navigation channel, an offshore island that supports coastal resilience), in a manner that lowers overall life-cycle costs, will increase the sustainability of infrastructure.

Principle 3

Comprehensive stakeholder engagement and partnering are used to enhance project value - Stakeholder engagement plays an important, even critical, role in the governance of infrastructure projects. The level of investment and sophistication employed in the engagement process directly contributes to the degree of success achieved through the engagement. Early investment in stakeholder engagement should be used to inform the conception and design of a project.

Such engagement will provide important information about the values of interest to stakeholders and how those values can be generated by the project, in respect to the three pillars of sustainability. Furthermore, early engagement can help identify project partners who are interested in making contributions or investments toward particular values the project could produce (e.g. partnering with an NGO to perform ecosystem restoration as a part of the project). Pursued in this manner, stakeholder engagement can produce opportunities to increase the overall value of a project and to diversify the benefits produced across all three pillars of sustainability. This approach to stakeholder engagement is different to the historical use, which has been more focused on reducing conflicts over project costs, which in the context of this discussion includes the negative impacts associated with a project (whether social, environmental or economic). For example, stakeholder engagement has been used as a means to proactively engage environmental interests concerned about port infrastructure, flood protection and dredging in order to minimise the risk of project delays and litigation. The information and knowledge that is produced through active and robust stakeholder engagement provides a basis for increasing the overall sustainability of the project.

When the information leads to actions that increase overall project value, sustainability is enhanced. When these actions lead to reducing total project costs (including all monetary costs and non-monetary impacts), while producing the same level of benefit, the result is a more sustainable project and system. Likewise, actions that increase project value (in terms of social, environmental, and economic benefits) for the same (or lower) costs result in a more sustainable project.

Traditionally, dredging projects have been focused on a narrow set of functions and outcomes (e.g. land reclamation, port basins and channels, coastal development, flood protection, pipeline trenches). A design was made and the effects on the environment and other functions were assessed, where possible mitigated, and, if needed, compensated. Stakeholders entered the project process late, during the permitting stage, where they were informed about the design, with limited opportunity to influence the design. This approach has frequently led to conflicts, project delays and frustration, for the developer as well as stakeholders. Increasingly now, more and more projects are developed in a manner that is more inclusive of stakeholder perspectives. At first, the focus on stakeholders was driven by aims to reduce the risk of project delays and lengthy procedural conflicts, but more recently this approach has evolved to include the mind-set of co-creation. In this mode of stakeholder engagement, values are created not only with regard to the primary motivation for the project (e.g. a particular set of economic outputs), but also to address stakeholder interests and values. This approach leads to value-added design and innovation, which will produce projects that are beneficial in regard to people, planet and profit (Elkington, 1997).

The practical contribution of dredging companies

Environmental impacts can have consequences that affect other marine users. The livelihood of local fishing communities may be affected by decreased fish stocks due to prolonged turbidity or deterioration of their fishing grounds. Coastal communities may be deprived from inhabitable land, cultural sites and natural wealth due to erosion or salinisation. Addressing these impacts is a requirement for project permits in many countries. Below are examples of dealing with these impacts.

Quantity of sand extracted

Between 1990 and 2023, dredged sediments were placed onto intertidal habitat to achieve both habitat restauration and coastal protection objectives at Horsey Island on the eastern coast of England. Sand and silt from capital and maintenance dredging at the nearby ports of Harwich and Felixstowe was used to create a mix of habitats including mudflats, marsh and a shingle spit to be used by nesting birds. The project has demonstrated that the environmental benefits can persist over decades. More case studies were collected by the CEDA Working Group on the Beneficial Use of Sediments.

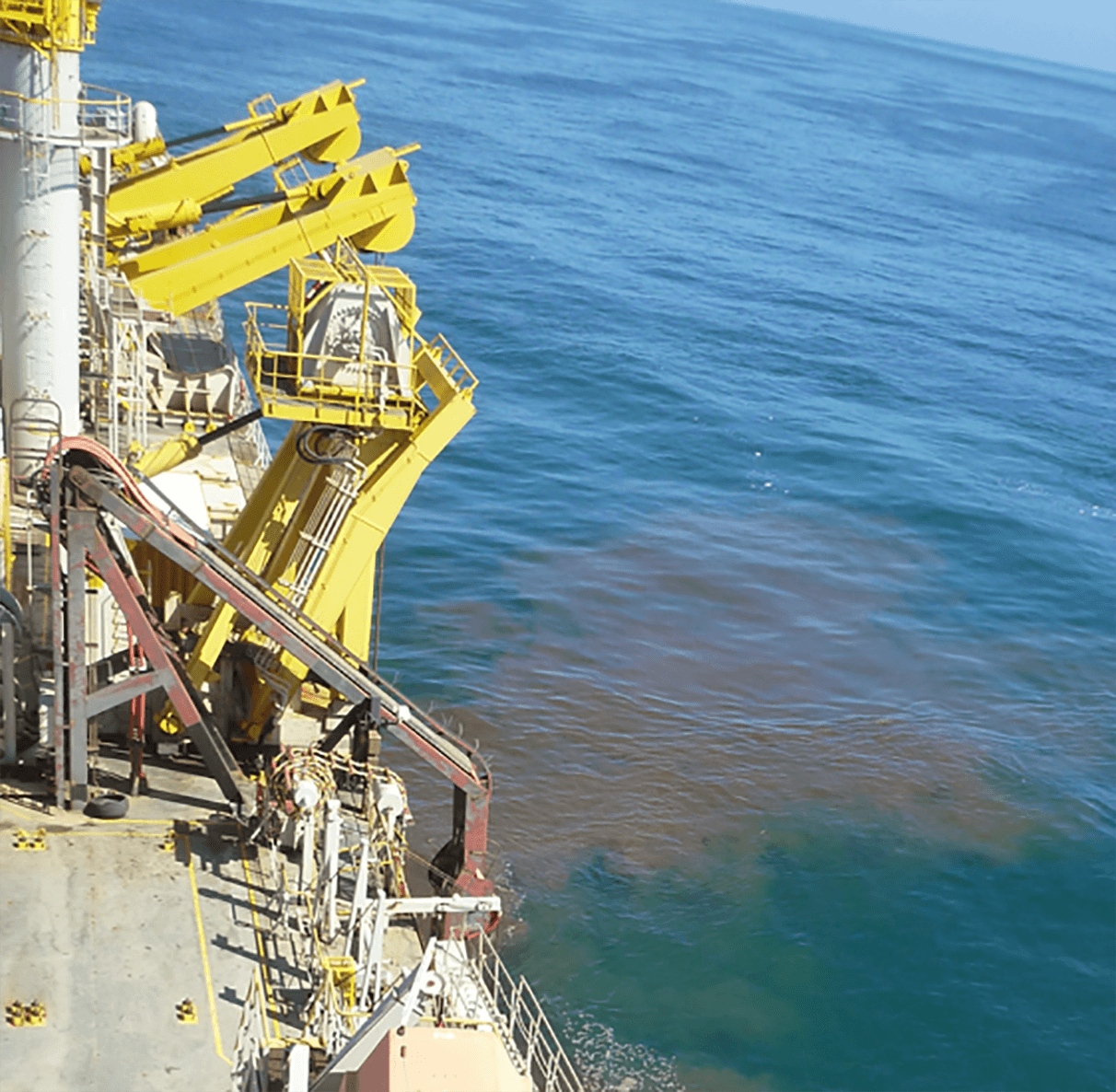

Loss or degradation of marine habitats inside the dredging zone

For the extension Maasvlakte 2 of the Port of Rotterdam, 220 mln m3 of sand was Extracted between 2009 and 2013. The maximum extraction depth was 20 m below seabed, which is tenfold of the traditional limit. This reduced the directly impacted area from 110 km2 to 11 km2. Two sandbars mimicking natural sand waves were left behind after extraction to increase habitat heterogenity. This is one of the optimisations researched in OR ELSE (recommendations for Ecosystem- based large-scale sand extraction) a consortium of 21 partners funded by the Dutch NWO programme.

Nature-inspired design

In Atafalaya River (USA), Dredged sediment is placed in the middle of the river, just upstream a natural shoal, and contributes to the formation of an island. In 10 years, a 35 hectare island was created that hosts a rich wildlife habitat with access for recreation and a better aligned navigation channel.

Also prohibiting sand extraction in vulnerable habitats, has an inevitable impact on the livelihood of local communities. Even if these activities are illegal, they provide the means

for survival of many of the local population. Any change in regulation to protect the environment should therefore be accompanied by measures to provide local employment.

These stakeholder impacts can be mitigated with the right regulations and ESIA procedure in place. In most projects, these regulations and procedures are beyond the scope and responsibility of contractors, but they can exercise due diligence and leverage and assist project owners with that responsibility.

A dredging project is short-lived and requires large deployment of human resources and equipment, often in little-developed areas. Yet it contributes significantly to the local economy in the form of:

- salaries for local workforce;

- local expenses (office, housing, transport, catering);

- local purchases and subcontracts (fuel, civil construction, fabrication, equipment rental); and

- tax revenues (import duties, royalties, withholding tax, corporate tax, personal income tax on salaries).

- onboarding and awareness training of local workforce with focus on health and safety, environmental care, diversity, equality and respect;

- training of local workforce when gaps are identified between required and available skills;

- selection and training of local suppliers based on labour and human rights, biodiversity, emissions, waste management and business ethics;

- advertisement of supply opportunities in local media;

- unbundling of contracts into units that are tailored to the local market; and

- engagement in local community projects.

Examples of these contributions are:

Stakeholder engagementPort Philip channel deepening project, Melbourne, that involved the removal of 23 mln m3 of sediment of which 3 mln m3 was contaminated, was met with strong and continued opposition. The client and contractor formed an alliance contract to share responsibilities and risks, and also the communication effort, leading to successful completion of the project. Stakeholder acceptance of the project was a result of the accurate and transparent public communications which included public consultations, public hearings, a dedicated website, a 24-hour toll-free telephone number, weekly press conferences, media releases, mailing lists, signage around the bay and notices to mariners. A vessel tracking system and online video data was used to prove that the operations proceeded in accordance with the environmental management plan.

Rebuilding villages after a floodAround 70,000 people suffered from coastal flooding and erosion hazards in Demak, Indonesia and entire villages have been swallowed by the sea. Many people have experienced a major loss in income, reaching up to 60-80% in some villages. Also, the agri- and aquaculture sectors which are key economic engines in Indonesia have suffered multi-billion dollar losses. A project was launched to support the villagers through Building with Nature. The strategy for the area was to restore the sediment balance and through that, the mangrove habitat by constructing permeable brushwood dams, in the near future, these dams will be overgrown by the mangrove forest. The results of the current BwN activities in the Demak district are encouraging. Sediments are indeed being trapped, restoring the coastal sediment balance and the mangrove habitat locally. The first mangrove seedlings have naturally established.

Sustainability for dredging practice: From philosophy to action

Dredging is connected to several SDGs, such as those related to navigation, coastal protection, and flood risk management. The dredging industry is increasingly recognising the need to incorporate these goals into the infrastructure development process and communicate how projects align with the SDGs.

Climate change continues, energy transition is a fact, the growing world population calls for more sustainable cities and the need for food will increase. The demand for dredging will only increase, therefore, continuing with responsible dredging projects is key to sustainable development. The industry will continue to advocate for sustainability and promote dredging for sustainable infrastructure along with conducting more research on the topic to better projects that truly contribute the UN Sustainable Development Goals.